The Moveable Marquee

Notes on Classic Cinema

Issue # 59 / December 1, 2025

Contents of this Issue:

Entrée: My Modus Operandi, and the Beginning of Narrative Film

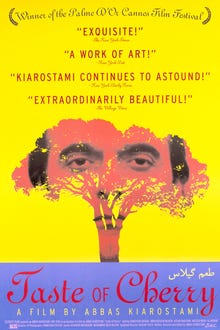

Film Commentary: To Help a Man Die: Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry

Classic Film Capsules: Jason and the Argonauts; The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser

Quote: Brian Desmond Hurst

Entrée: My Modus Operandi, and the Beginning of Narrative Film

Occasionally I like to restate the mission of The Moveable Marquee. When I began in 2023 my idea was to draw attention to classic films that are less often written about in mainstream reviews and commentaries. That is still my central motive. Therefore, you won’t find commentaries here on Casablanca, The Wizard of Oz, The African Queen, Stagecoach, Chinatown, or Citizen Kane, although I love those films. I used to teach a course at Rochester Institute of Technology, “Writing about American Film,” and I’ve screened Casablanca more times than I can remember.

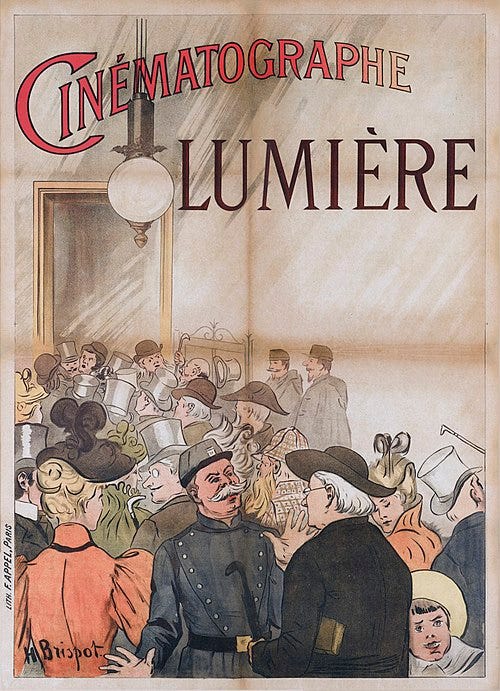

Film, and I mean worldwide cinema from its dawn with the Lumiere brothers until the present day, is an enormous body of literature, and any attempt at film literacy will enrich the mind and especially the soul. I aim my commentaries at anyone who is interested film, from scholars to those with a mere budding fascination. And I welcome responses from anyone.

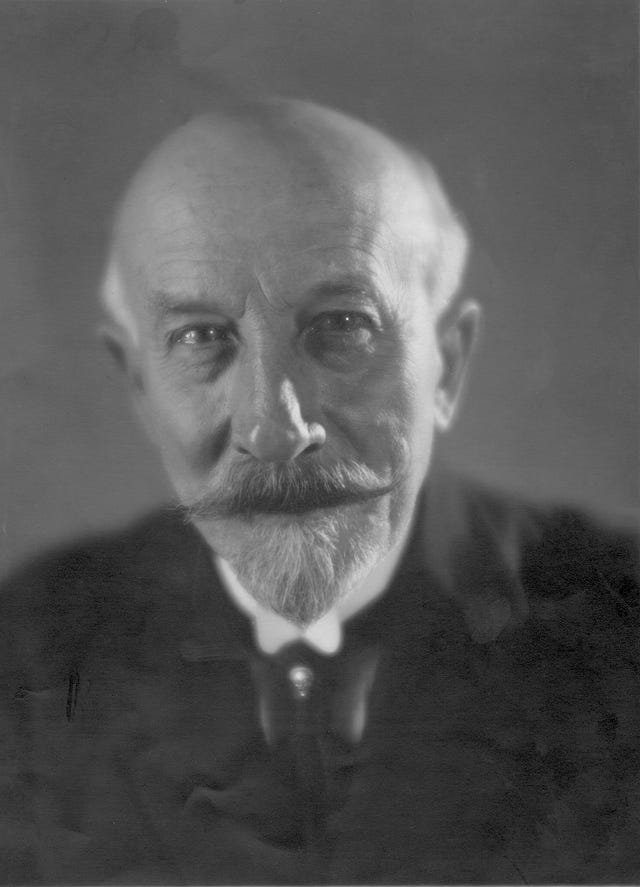

Georges Méliès

Those first films by the Lumiere brothers were less than a minute long, on such subjects as a crowd of workers leaving the Lumiere factory, and a train arriving at a station—which startled their audience and made them jump out of their seats thinking they were about to be run over. Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky, writing about those first films, said, “for the first time in the history of the arts, in the history of culture, man found the means to take an impression of time.”

For me, narrative film begins with Georges Méliès, a French stage magician who attended the Lumière brothers’ historic first public screening in 1895. Right away he realized film’s potential in magic performances and special effects, and as a vehicle for story. You can find much of his surviving work on YouTube and Prime, including my favorite, A Trip to the Moon (1902).

The moon, by the way, figures wonderfully in the end of Abbas Kiarostami’s A Taste of Cherry, the focus of my film commentary in this issue.

Film Commentary:

To Help a Man Die: Abbas Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry

By Steven Huff

Taste of Cherry (1997). Directed by Abbas Kiarostami. With Homayoun Ershadi, Safar Ali Moradi, Mir Hossein Noori, Abdolrahman Bagheri. Written by Abbas Kiarostami. Cinematography by Homayun Payvar. Music: “Saint James Infirmary,” performed by Louis Armstrong. In Persian and Kurdish with English Subtitles. Color. 1 hr., 35 mins.

Streaming on Criterion and HBO Max

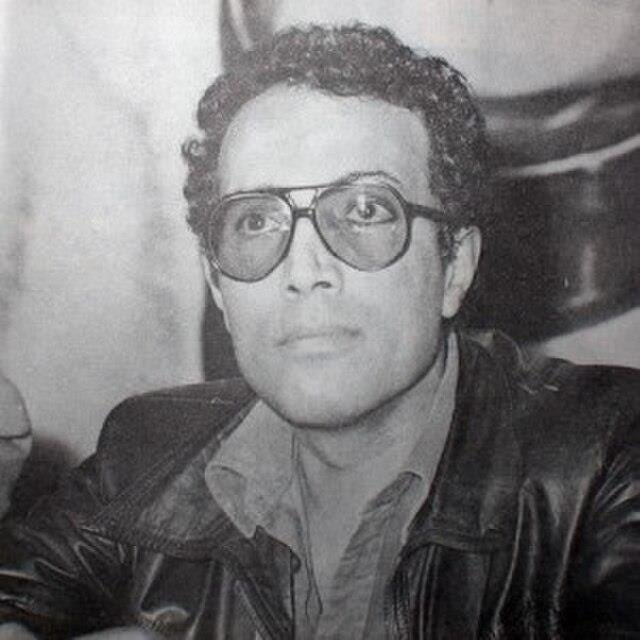

Abbas Kiarosami (1940-2016) was among the vanguards of the film division of the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (also including Amir Naderi and Noureddin Zarrinkelk), which in the 1970s became a center of Iranian filmmaking. Over his career, his influence increased dramatically, not only in Iran but in world cinema. In 1997 Phillip Lopate wrote, “In terms of international art cinema (though Americans don’t know it yet), we are living in the Age of Kiarostami.” Lopate credits Kiarostami with thoughtful, emotionally powerful work which “reinvents neorealism (amateur actors, slice-of-life stories),” with modest budgets and large themes.

The films, Where is the Friend’s House (1987), And Life Goes On (1992), and Through the Olive Trees (1994), make up his Koker Trilogy, focusing on the people of a small Iranian town, and are landmarks of Iranian cinema. The Taste of Cherry (1997), which won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival the same year, is generally considered his greatest film. It stars Homayoun Ershadi in his first role, who, unfortunately, died on November 11 of this year.

Abbas Kiarostami

Taste of Cherry opens with a middle-aged man (Ershadi) driving slowly around a suburb of Teheran. He offers a ride to a young Kurd (Moradi) in the uniform of the Iranian Army. The soldier is grateful to get the lift because he must report to his barracks by 6 pm, and it’s now 5. But the driver—who introduces himself as Badii—seems to have something up his sleeve. While promising to deliver the soldier to his barracks on time, Badii drives him into the sandy hills outside of the city, stops the car on a dirt road and makes a proposition. He points to a hole that he’s dug beside the road and says that he’s going to climb into it that night and commit suicide by taking a lethal quantity of sleeping pills. He wants the soldier to come back in the morning and check on him. If Badii doesn’t respond, the soldier is to use a shovel to throw dirt over him, then help himself to money that the man will have left there—200,000 Tomans (about $200). The soldier refuses, but Badii keeps pressing him until he panics and bolts from the car, running back over the hills toward Teheran.

Next, Baadii picks up a young Afghan seminarian (Noori) and makes the same offer. The seminarian tells him flatly and firmly that suicide is against Islamic law and that he won’t help him; instead, he tries to deter him. Badii, who is becoming peevish at this point, snorts that he doesn’t want a religious lecture. He does not explain to anyone his anguish or why he wants to end his life. What’s going on deep in his mind and soul is one of the enigmas that nourish the story.

Kiarostami’s juxtaposing Badii’s plight with soldiers marching though the hills, with men on heavy machinery digging up earth—mechanical aspects of ordinary life—emphasizes his insulation.

Finally, Badii picks up a kindly old taxidermist (Bagheri) on his way to his job at the Natural History Museum. The elderly man agrees to do the deed only because his son is ill and he needs the money for his care. But as they ride, the old man tells him a story of a time when he himself, after a fight with his wife, was going to end his life. One morning before sunrise he was about to hang himself from a mulberry tree when he tasted some of the fruit, and the sweet sensation moved him. As he ate the berries the sun was rising. “What a sun, what greenery!” He took mulberries home and gave them to his wife and they ate them together. After that experience, he came to appreciate sunrises, the moon and stars: the taste of life.

“But you want to give it all up,” he says. “You want to give up the taste of cherries?”

The old man’s story, essentially a philosophy of awakening, gets through to Badii to some extent, or at least makes him uncertain of what he’s going to do. After dropping the taxidermist off at the gates of the museum, he suddenly turns and drives back and, quite earnestly, asks the old man to throw two stones at him in the morning to rouse him. The old man, a bit annoyed at being distracted from his work, replies that he’ll throw three.

That night Badii takes a taxi out to the spot in the hills. The camera follows the taxi ponderously in the dark. Badii gets out and sits on the roadside and lights a cigarette and then climbs into his hole. Thunder rolls and it begins to rain. The moon is rolling through the clouds above the lights of Teheran.

Perhaps the larger unknown in this story is not what motivates Badii to commit suicide, but whether he actually goes through with it. In fact, Kiarostami doesn’t end the film with the scene of Badii climbing into his hole, but with a sudden switch to grainy video footage of the film crew working in broad daylight and Ershadi himself walking casually about, offering a cigarette to Kiarostami, all to the music of Louis Armstrong playing “Saint James Infirmary.” This ending has been controversial and puzzling to many. I think that it serves as a coda that does two things at once: it ironically avoids closure, that is, we are not to know if Badii ends his life; and it tells us that, essentially, this is just a story.

Joseph Campbell, in a PBS interview with Bill Moyers, said that people do not actually seek meaning in their lives, but rather a full experience of being alive. The taxidermist (who, ironically, deals professionally with dead animals) is a bit of a sage. He doesn’t give Badii a philosophical reason to stay alive, rather his is a wisdom of sensual experience, the astonishment of sweetness and sunrise, sensations available to anyone who does not reject them. Badii may be too closed up to hear such things.

That he’s so intent on enlisting another person in his purpose suggests that he is at least half-hoping to be talked out of it, even though he rejects the attempts by the seminarian and the taxidermist to do just that. Yet, there is his ardent request that the taxidermist make a greater effort to rouse him. And there we see that this film is as much about Badii’s isolation, his loneliness—a man who can offer no more information about himself than that he wishes to die—as it is about suicide. Maybe he’s of two minds, one which wants to die and one which wants to live. I knew a man once who, distraught, attempted suicide, and when he woke up later in a hospital, was ebulliently happy that his life had been spared—almost as if there were another self who had tried to kill him.

Taste of Cherry is a masterpiece of storytelling, and of ambiguity. It’s not that it stands alone as a film about someone on the edge of suicide. Yet Kiarostami handles the subject adroitly, without sentimentality or melodrama. He realizes that when an individual reaches the brink of suicide, rational, moral, or philosophical entreaties may not help. And he knows better than to give us answers. Instead, he shows us a character who professes his resolve to die, while also trying fervently to involve others—ostensibly sane people—in the deed, like planning a bank robbery and inviting your shrink to go along. Badii might take the pills. He might take only enough to sleep. Or he might just lie there in the rain and look at the moon.

Sources and Paths to Further Exploration:

Erfani, Farhang. Iranian Cinema and Philosophy: Shooting Truth. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Dabashi, Hamid. Close Up: Iranian Cinema, Past, Present and Future. Verso, 2001.

Nafisy, Hamid. “Hamid Naficy on Abbas Kiarostami.” Criterion video essay, 2020.

Lopate, Phillip. “Abbas Kiarostami: Through the Olive Trees and Taste of Cherry.”. My Affair with Art House Cinema: Essays and Reviews. Columbia University Press, 2024.

· Thanks to Barry Voorhees for editing

· Thanks to Tim Madigan for suggestions.

Classic Film Capsules:

Jason and the Argonauts (1963). Directed by Don Chaffey. With Todd Armstrong, Nancy Kovack, Laurence Naismith, Gary Raymond, Nigel Green. Streaming on Prime and Tubi.

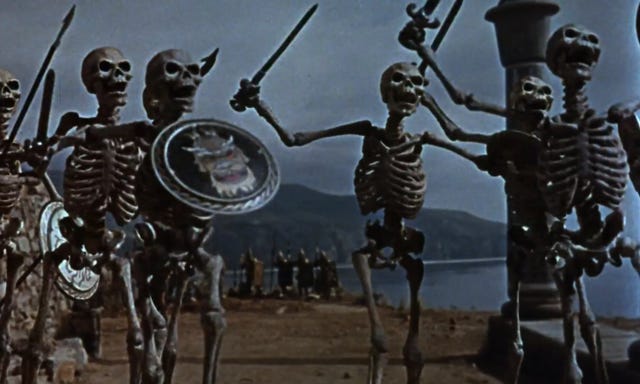

I saw this film last month at the Dryden Theater at the George Eastman Museum in a series on stop-motion animation. They screened Martin Scorsese’s personal print—his vast film collection is stored in their vault. Anway, it was the first time I’d seen it since I was a kid. I’m not being merely nostalgic to say that this story of Jason (Armstrong) and the bewitching Medea (Kovack) who betrays her royal family and all of Colchis by helping him to steal the Golden Fleece is pure pleasure. Unlike in the myths, it is more Jason’s prowess with the sword than Medea’s witchcraft that enables him to defeat the hydra serpent and the army of skeletons. Niall MacGinnis and Honor Blackman play a comic Zeus and Hera looking down on the whole mess. Even Hercules (Green) is more buffoon than hero. But what is especially wonderful about this film is the intricate work of the stop-motion animation master Ray Harryhausen, who makes the skeletal warriors and the giant bronze Talos warrior happen. In this era of computer- generated images, one might think these special effects look dated, but they should be admired for an enormous accomplishment, done the hard way. (I should mention that stop-motion animation is still in use by some filmmakers.) The fact is, the miraculous is in the eyes of the beholder: sixty-two years ago, this movie made our eyes pop out.

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), also known as Every Man for Himself and God Against All (1974) Directed by Werner Herzog. With Bruno S., Walter Ladengast, Brigitte Mira. West Germany. Streaming on Criterion, Fandor, Tubi, Prime, and other services.

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser is based on “historical” events, despite some disagreement concerning what elements of the story actually occurred. In any case, Kaspar Hauser (1812-1833) was truly an enigmatic and tragic individual. Hauser, so the story goes, was kept chained in a dark cellar for the early years of his life, during which time he never experienced fresh air, never saw a tree. At the age of seventeen his captor dumped him in the middle of Nuremburg with a letter stating that he, Hauser, wished to become a valiant cavalryman like his father. He was barely able to walk or speak—an extreme case of arrested development. He came under the care of schoolmaster Friedrich Daumer, who did his best to educate and socialize the unfortunate young man despite his impulsiveness, manipulativeness and seeming desire to retaliate against society. While in Daumer’s care he suffered a head injury from an attack he claimed was perpetrated by his original captor and was stabbed in the chest in the park by a person unknown. This is the basic story that Werner Herzog tells. Some scholars and doctors claim his wounds may have been self-inflicted to regain public sympathy that he felt was waning, while others cast doubt on the story of his early confinement. Nevertheless, Herzog’s film is engrossing, a bit in the vein of Francois Truffaut’s historical film Wild Child (1970) about a boy rescued from the wilderness in eighteenth century France and the doctor who attempts to acclimate him to society. In the role of Hauser, Herzog cast Bruno S. (1932-2010), the son of a prostitute who beat him and abandoned him to be raised in institutions. While a child, Nazi doctors experimented on Bruno, as they did on many children they considered mentally deficient. He became a musician and painter while working menial jobs to support himself and had a sporadic film career, including in Herzog’s Stroszek (1977). In the Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, he shows himself a capable actor. While he was older than the real Hauser, he had an essentially awkward and off-putting personality resemblant of the character he played.

#

Text: Copyright 2025 by Steven Huff

Quotes: “I am trisexual. The army, the navy, and the household cavalry.” —Brian Desmond Hurst.