The Moveable Marquee:

Notes on Classic Cinema

Issue # 57 / November 1, 2025

Contents of This Issue:

Entrée: Refound Cinema

Film Commentary: “Ghetto Verité: Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep.”

Classic Film Capsules: The Annihilation of Fish; Battling Butler; The Young One.

Quotes: from Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Douglas Sirk

***

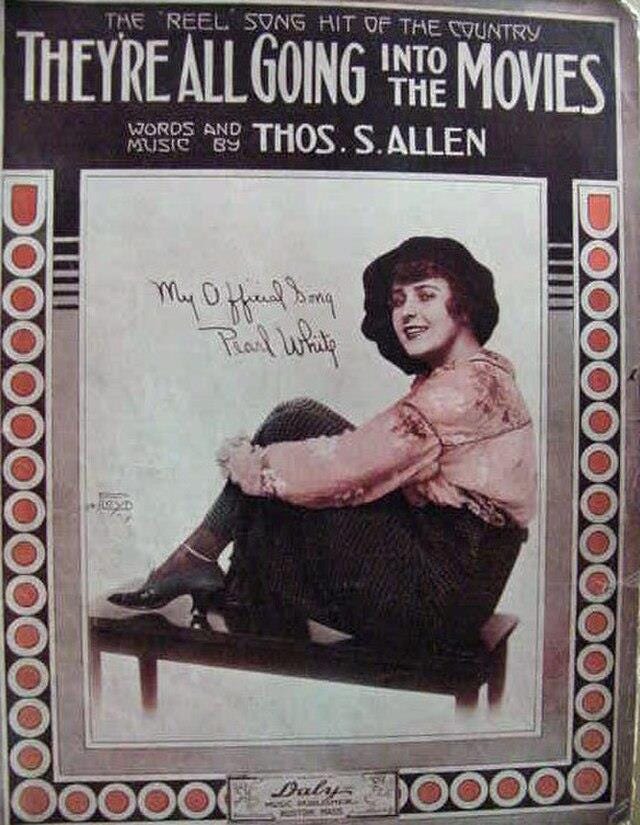

Entrée: Refound Cinema

Anthony Lane wrote in The New Yorker recently about the 39th annual film festival in Bologna, Italy, held this past June. It’s called Il Cinema Ritrovato, or in English, “refound cinema,” where old films are screened. Most are prints that have been restored locally at the laboratory of a film archive called the Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna. On the program were films as varied as Charles Chaplin’s 1925 The Gold Rush (there are more versions than one), Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep (1978).

A print of Georges Méliès’s Le Raid Paris-Monte Carlo en Automobile (1905, about an auto trip across France) was screened. Méliès (1861-1938), a professional stage magician, began making films shortly after seeing the Lumière brother’s historic first public screening of a motion picture in Paris in 1895. He may have been the first to give narrative structure to any film. It inspired Lane to reflect on an issue that I’ve thought about many times myself.

Lane asks, “Were we not being spun back in time and granted a chance…to hook up with the original audience? Did we not drink in this fizzy little movie as they had drunk it, a hundred and twenty years ago?” He says that to ask that question, one must confront another question that concerns all art restorations, in regard to audience. “I can kid myself that I enjoyed ‘Le Raid’ just as a Parisian would have done in 1905; as likely as not, though, we were laughing at different jokes.”

Lives were different then. Assumptions and experiences were different. The world was different. Though I react deeply to William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives, I’m not experiencing it as someone did in 1946 who had just returned from World War II, or someone whose loved one didn’t make it back, or indeed, anyone who lived through the war. I could go on at great length about this issue.

And then there are films, many of them, that never had anything like a full audience in their own time. One is the previously mentioned Killer of Sheep, the subject of my commentary in this issue. For the first thirty years of its existence, it had no effective commercial distribution.

***

By the way, if you haven’t seen Blue Moon, I highly recommend it. A new film by director Richard Linklater is always an event. But this biopic with Ethan Hawke as Lorenz Hart at the party following the opening of Oklahoma!—after Richard Rogers had dropped him and replaced him with Oscar Hammertstein—is a masterwork. Don’t miss it.

Film Commentary:

Ghetto Verité: Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep

By Steven Huff

Killer of Sheep (1978). Produced, directed, written and filmed by Charles Burnett. With Henry Gayle Sanders, Kaycee Moore, Charles Bracy, Angela Burnett, Eugene Cherry, Jack Drummond. Music by various artists—see below. Black and White. 1 hr., 20 mins.

Streaming on Criterion and Prime.

About twenty-five minutes into Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, two men knock on the door of a shabby white house in the Watts section of Los Angeles. When Stan (the story’s main character) comes out to talk to them, they offer him the chance to join them in an ugly crime caper. They want a third partner, someone who won’t “blush to murder.” He’d make some money. Stan refuses, angrily. When his wife (Moore) comes out and hears what’s being discussed she rages at them. One of the men says. “We’re just trying to help the n----- out.”

Killer of Sheep goes in a different direction from the Blaxploitation films of its era, or most American films of the time with prominent black characters. Although two men attempt to lure Stan into a crime, no murders or other major crimes actually occur in the film. No police presence. Just people struggling to get by. Initially, the film seems loose, and it’s hard to see where the story is going; but then the medley of scenes falls subtly into place.

Charles Burnett Photo: Studio Harcourt

Stan (Sanders) is certainly struggling financially but he’s not going to risk getting in trouble along with two crooks packing guns.

“Man, I ain’t poor,” he protests to a friend. “I give things away to the Salvation Army. You don’t give nothin’ away to the Salvation Army if you’re poor.”

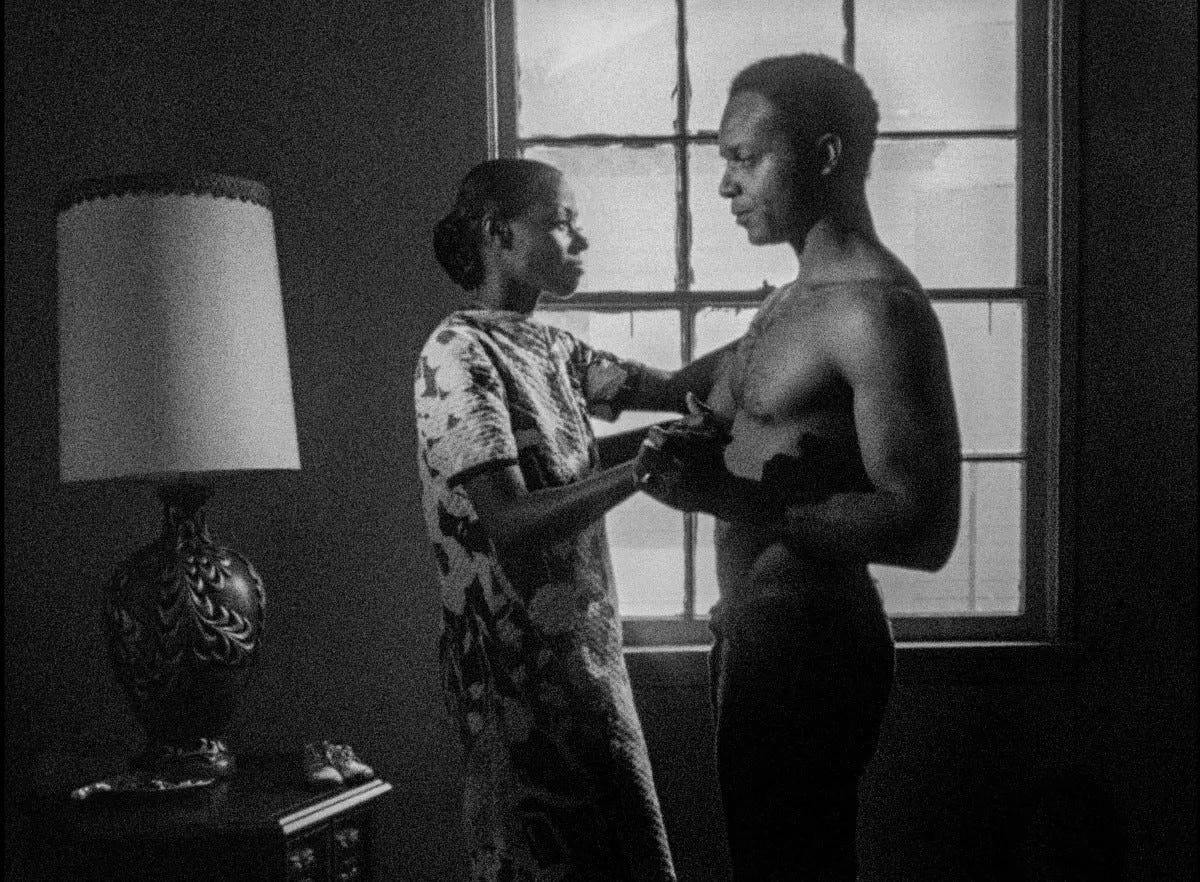

There are numerous signs that money is scarce for Stan and his family: holes in the living room wall, the kitchen table is paint splattered. He doesn’t have a car that runs or a bank account. He must cash his paychecks at a local liquor store. His job in a slaughterhouse (the source of the film’s title) is apparently steady, though probably not well paid. The disturbing scenes there, the pitiless hanging of sheep by their legs, cutting their throats, and carting away the guts, symbolize how harshly and quickly life can end. Stan is exhausted, depressed, and can’t sleep; he’s distant from his wife, which leaves her frustrated. “I’m workin’ myself into my own hell,” he tells his friend Bracy.

“When you last been in church?” Bracy asks. Stan thinks for a moment before answering, “Back home.” He doesn’t elaborate on where that place was, but we get a sense of the family’s economic and racial displacement. Where they live isn’t quite home. Burnett himself was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi before his family migrated to LA in search of work.

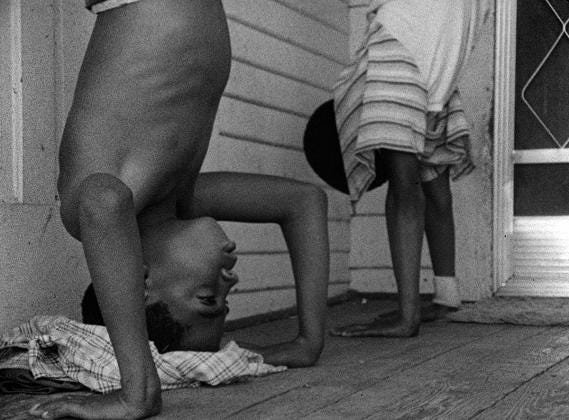

Most of what Stan gets into is unlucky. He buys a used car engine off the kitchen floor of a shady character. He and his friend Eugene lug it down three flights of exterior stairs and set it in the bed of Eugene’s pickup truck. As soon as the truck lurches into gear, the engine falls on the pavement. The block is cracked. It’s useless. They drive away, leaving the engine in the street. One of the film’s most striking progressions follows that fiasco. Stan is walking home through an alley while high above his head kids are leaping from the roof of one building to another. There’s reckless felicity in youth. Things get serious when you’re an adult. “Life is too soon over,” Stan says.

In small ways we see Stan begin to lift out of his depression. Cuddling with his daughter in his lap. Slow dancing with his wife to Dinah Washington’s “This Bitter Earth.” By the end he wears a sardonic smile at work as he herds sheep to slaughter, while Washington sings “Unforgettable.”

Henry Gayle Sanders and Kaycee Moore

Killer of Sheep has the feel of cinema verité, its black and white documentary style alive with the tempo of everyday life in the neighborhood: kids in a vacant lot throwing rocks at a freight train, Stan talking through his blues, listening to his wife’s frustrations. A drive to the racetrack in Eugene’s car (the only scene filmed outside of Watts) ends with a flat tire and no spare; they drive back home on the rim.

Director Burnett made his film—which Jonthan Rosenbaum says is “conceivably the single best feature on ghetto life”—on a succession of weekends (continuity must have been a nightmare) in 1972 and ‘73 with mostly non-professional actors. He submitted it for his master’s thesis at UCLA. Burnett was part of the so-called LA Rebellion at the time, which was a group of Black film students who got together and decided that the industry was not going to give them the opportunity to make realistic films about the Black experience in America and that they were going to have to do it on their own. Mutual moral support.

The results were, in addition to Killer of Sheep, Haile Gerima’s Harvest 3000 Years, Jamaa Fanaka’s Emma Mae, and Billy Woodberry’s Bless Their Little Hearts. An enormous output from a small group. And those were just the first films from these four: they all went on to further filmmaking careers. When Killer of Sheep premiered in 1977, it had no real commercial distribution partly due to legal battles over rights to music used in the soundtrack, pieces that truly enrich the film, including Paul Robeson’s “The House I Live In”, “Louis Armstrong’s “West End Blues,” Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Reasons,” Elmore James’s “I Believe,” Rachmaninoff’s “Piano Concerto #4,” and, most poignantly, Dinah Washington’s songs. It scored a review in the New York Times by Janet Maslin, who knocked it down for monotony and a lack of coherence.

It was generally seen only at film festivals until 2007, when a restoration and transfer to 35mm (from its original 16mm) breathed new life into it, and then it played the arthouse circuit in more than two-hundred cities. Cinephiles of the world were impressed. It was named one of the 100 Essential Films by The National Society of Film Critics, and one of the first fifty films enshrined as a national treasure by the Library of Congress and was listed as one of the 100 Greatest American Films by the BBC. Astonishing for a master’s thesis project. More recently it was released on DVD and on streaming services.

It’s easy to note its influences. Certainly, Italian Neo-Realism, such as Roberto Rossellini’s Rome Open-City (1945) and early French Nouvelle Vague, such as Agnes Varda’s La Pointe Courte (1954). Yet it covered important new ground: the Black experience in LA in the ‘70s, barely a decade after the Watts riots that left dozens of people dead.

Killer of Sheep holds up fifty years after it was made. Its characters are flesh and blood filmed with the integrity of an earnest man with a script and a camera.

Sources and Paths to Further Exploration

Maslin, Janet. “Screen: “Killer of Sheep” is Shown at the Whitney: Nonprofessional Cast.” New York Times, Nov. 14, 1978.

O’Sullivan, Marie. “Film Review: Killer of Sheep.” The Movie Isle: Film for Your Deserted Island. April 17, 2025. themovieisle.com/2025/04/17/film-review-killer-of-sheep-1977/

Rosenbaum, Jonathan. “Killer of Sheep” From the August 3, 2007 Chicago Reader.

Stevens, Dana. Black Sheep: A Legendary Film from 1977 Gets Its Due. Killer of Sheep Reviewed. Slant magazine. Slant.com, March 30, 2007.

Thanks to Barry Voorhees for editing

Thanks to Tim Madigan for suggestions.

Classic Film Capsules:

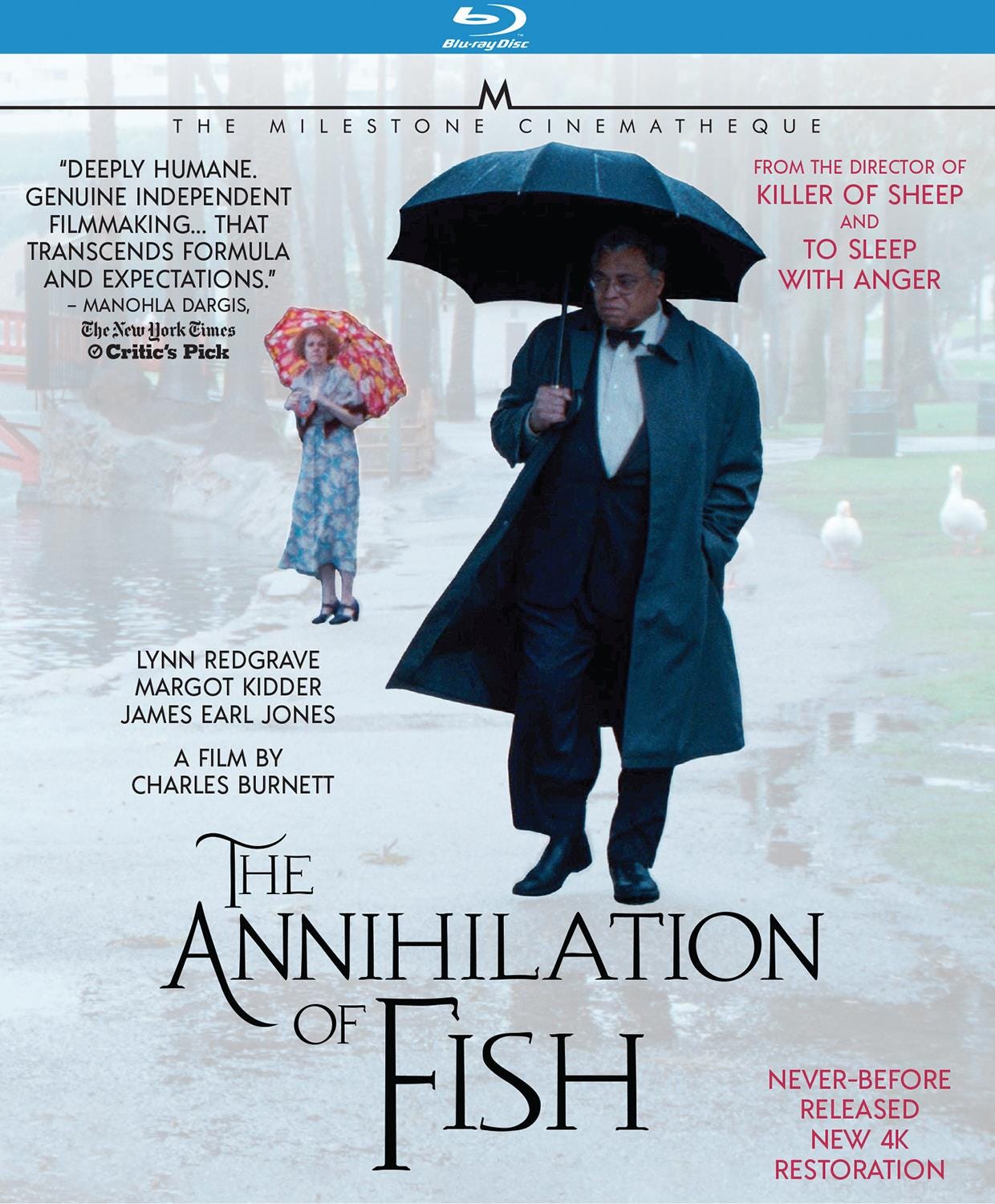

The Annihilation of Fish (1999). Directed by Charles Burnett. With James Earl Jones, Lynn Redgrave, Margot Kidder. Streaming on Criterion and Prime.

I thought it appropriate to add another film from Burnett. A man named Fish (Jones) is a Jamaican immigrant in Los Angeles. He wrestles physically with a demon that only he can see. Poinsettia (Redgrave) is also a case, believing herself to be the lover of the likewise invisible Giacomo Puccicni. Both are new tenants in an apartment house run by a lonely widow (Kidder). Fish shakes the house with his wrestling, while Poinsettia shrieks out Madama Butterfly which she claims Puccini wrote for her. They fall into a truly offbeat love story that, as they trade psychoses, explores issues of loneliness, advanced-age-romance, triumph over old hauntings, and revivification. Burnett runs his romantic comedy around erratic corners while maintaining a harmonic balance to the story. This film is another example of why Burnett, director of Killer of Sheep, is considered a master. Unfortunately, distributors didn’t pick it up, and like so many great independent films it was years getting its due—in fact, Redgrave did not live to see it. Now a restored version is available on DVD and Blu-ray, and on streaming services. Not a film to miss.

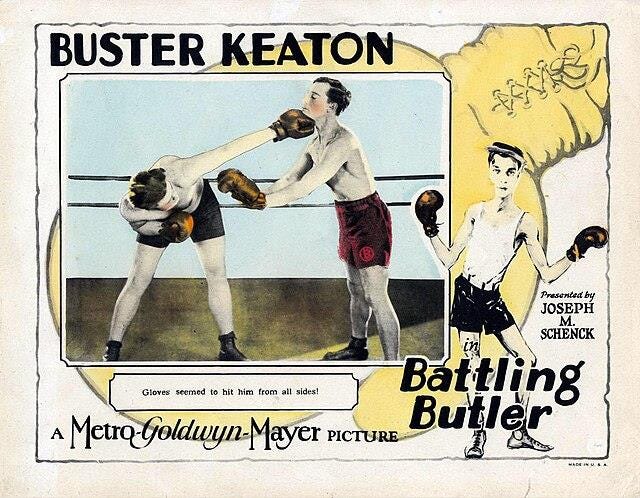

Battling Butler (1926) Directed by Buster Keaton. With Keaton, Sally O’Neil, Snitz Edwards, Francis McDonald. Silent. Streaming on Criterion, Filmbox, Tubi, and Prime.

I haven’t focused on a silent film in a while, so I’m including a great one here. Of all Keaton’s feature-length films, only Seven Chances has a more unlikely premise. It’s the only one of his films made from an original stage play. Young, wealthy Alfred Butler (Keaton) is sent on a hunting and fishing trip by his father hoping that roughing it will finally make a man of his insouciant son. Of course he takes his ultra-obsequious valet (Edwards) along. On a wooded mountain, he meets the woman (O’Neil) whom he wants to marry and tells his valet to “arrange it.” But her rough mountain family does not want a weakling in their clan. So, the valet convinces them that Alfred Butler is actually Battling Butler, the boxing champ who is rising to fame. Now he’s in big trouble because he must perform elaborate fakery to save face; and worse, when the real Battling Butler (McDonald) finds out about the imposter, he tells poor Alfred he has to fight a big brute named The Alabama Murderer to keep his championship. Overshadowed by his more famous films, The General and Sherlock, Jr., this one is nevertheless farcical and very funny. Keaton does some startling boxing when he and Battling Butler square off near the end of the film. By the way, Snitz Edwars plays Florine Papillon, the only comic role in Rupert Julian’s The Phantom of the Opera (1925).

Luis Buñuel / Photo by Man Ray

The Young One (1960). Directed by Luis Buñuel. With Bernie Hamilton, Zachary Scott, Key Meersman, Crahan Denton, Claudio Brook. Streaming on YouTube.

A Black man named Traver (Hamilton) is a clarinetist in a traveling jazz band. In a Carolina coastal town, he’s falsely accused of rape. Running to escape a lynch mob he steals a small boat and travels as far and fast as he can until the outboard motor runs out of gas. He paddles to shore on an island that is a wildlife preserve and hides in the woods. A gamekeeper named Hap (Scott) lives in a cabin on the island with an illiterate teenage girl named Evvie (Meersman), whom he abuses at night. When Hap goes ashore for a meeting, Traver comes to Evvie to beg food. Hap, a thoroughgoing racist, comes home and finds supplies and a shotgun missing and goes in search of the fugitive. A violent, grimly ironic, sometimes almost comic, contest ensues, complicated by the arrival of Rev. Fleetwood (Brook) to baptize Evvie. One of Buñuel’s least-known films—made during the Civil Rights Movement—The Young One is an intriguing film about the Jim Crow South, also taking on issues of pedophilia. Singer Leon Bibb provides the pithy folk spiritual, “Oh, Sinner Man (where you gonna run to)” for the soundtrack.

***

Quotes:

“[T]he gangster environment is a bourgeois setting turned on its head, so to speak. My gangsters do the same things that capitalists do except they do them as criminals. The gangster’s goals are just as bourgeois as the capitalist’s.” —Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

“This is the dialectic—there is a very short distance between high art and trash, and trash that contains an element of craziness is by this very quality nearer to art.” —Douglas Sirk.