The Moveable Marquee

Notes on Classic Cinema

Issue # 51 August 1, 2025

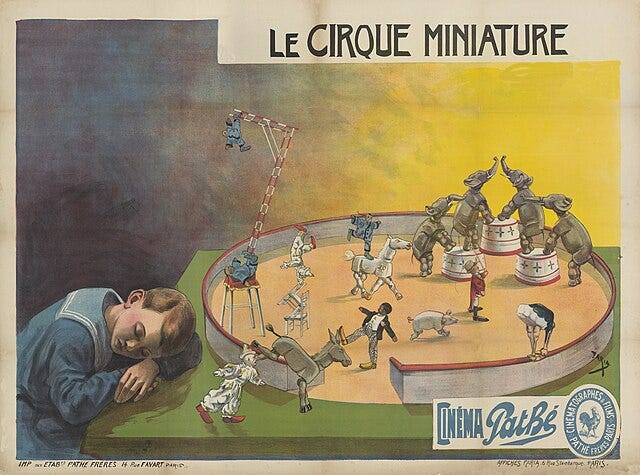

Poster for The Miniature Circus (1908) art by Cândido Aragonez de Faria

In this issue:

Entrée: The Literature of Film

Film Commentary: on Andrzej Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds

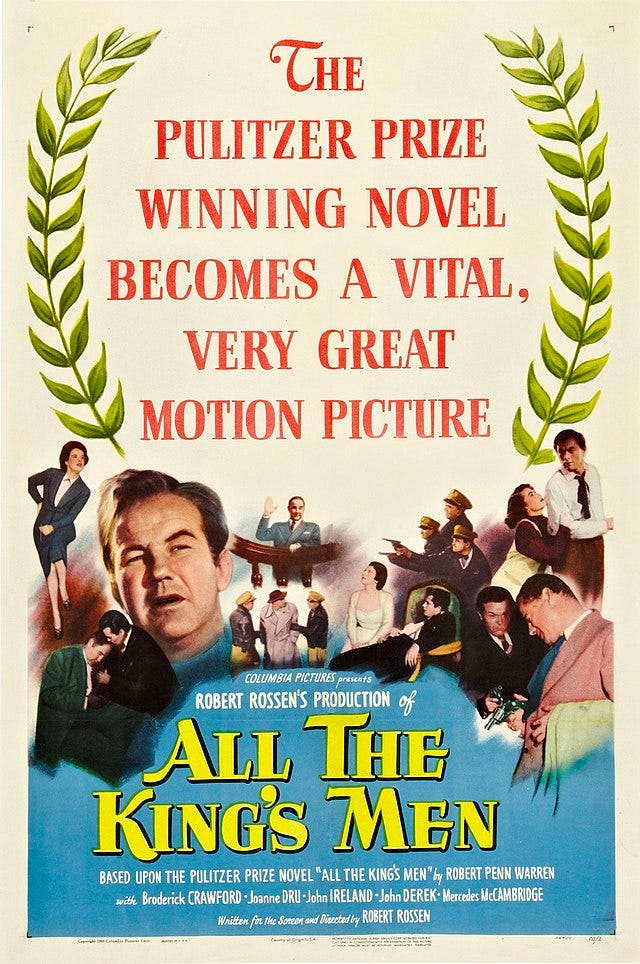

Classic Film Capsules: All the King’s Men; Taxi

Entrée: The Literature of Film

I used to teach a course at Rochester Institute of Technology called “Writing about American Film.” It was the most fun I’ve ever had teaching. Most students in my classes had never thought about movies as classics. Many had never seen a black and white feature. I always started the course with Casablanca, for two reasons. One was a local hook: Ingrid Bergman had been living in Rochester with her first husband when she landed the role of Ilsa. The other was more of an enticement: I’d never met anyone young or old who did not like Casablanca, and once I’d shown it to my class, I knew they’d pay attention when I showed other black and white films, such as Young Mister Lincoln, and The Magnificent Ambersons. After I showed The Searchers, one student told me that he’d never seen John Wayne before but now realized that the comedians he’d seen imitating him were spot-on.

I taught the last section of that class thirteen years ago, and when I think about it, I wonder how many of them remember the films. I don’t know if I succeeded, but I wanted to give them something like the enchantment I experienced in college when I took a course called “The Literature of Film.” In that class we watched Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly and Shame, Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, and the three movies that used to be called The American Trilogy: Cool Hand Luke, Bonnie and Clyde and Midnight Cowboy. I was already a film fan who frequented art house theaters in Buffalo. But it was in that class that I first began to think about film as literature, with its own language, themes, and symbology. And I eventually found a wealth of scholarship I could dive into.

No, I didn’t go to film school. I made my career in publishing. And I wrote books. I think it was F. Scott Fitzgerald who said that there are no second acts in American lives. In other words, we do not reinvent ourselves. Well, I think we do, and I think I am now somewhere between Act Seven and Ten. I publish The Moveable Marquee twice a month on the premise that film is literature and deserves the ennoblement that we give to books.

It is really not aimed at scholars, but rather at anyone interested in film, who would like to know more about movies and would like to be turned on to films that they might otherwise have missed.

And on that happy note, I give you Issue # 51, with a commentary on Polish director Andrzej Wajda’s third feature, Ashes and Diamonds (1958) followed by two capsules on Robert Rosen’s All the King’s Men (1949) and Roy Del Ruth’s Taxi (1931).

Film Commentary:

Where There’s a Will to Dance: Andrzej Waida’s Ashes and Diamonds.

By Steven Huff

Ashes and Diamonds (1958). Directed by Andrzej Wajda. With Zbigniew Cybulski, Ewa Krzyzewska, Adam Pawlikowski, Waclaw Zastrzezynski. Screenplay by Andrzej Wajda and Jerzy Andrzejewski from a novel by Andrzejewski. Cinematography by Jerzy Wójcik. Music conducted by Filip Nowak. Black and White. 1 hr. 43 mins. In Polish with English Subtitles.

Streaming on Criterion, Max and Prime.

Andrej Wajda was a giant of Polish cinema, recognized far beyond the borders of his country—which was behind the Iron Curtain for much of his career. His achievements seem especially impressive, given that he attained such heights while evading government disapproval for his dramatic chronicles of Polish life, history and sensibilities. Wajda (1926-2016) was 13 when, in September 1939, Poland was invaded by Germany from the west and the Soviets from the east. His father, a Polish cavalry officer, was one of many herded into the Katyn Forest and murdered by the Russian military, a topic of his 2007 film Katyn.

Andrej Wajda

Wajda studied painting for several years before enrolling in the famous Lodz Film School. He first came to international attention with his trilogy of Poland in World War II: A Generation (1955), Kanal (1957), and Ashes and Diamonds (1958). After the fall of the Iron Curtain, he made a couple films in France: Danton (1982) and A Love in Germany (1983), then returned to Poland for The Revenge (with Roman Polanski, 2002), Katyn (2007) and Tatarak (2009). He made more than fifty feature films in all.

He acknowledged his debt to American directors, particularly John Ford, William Wyler and Orson Welles. I think the influence of Welles is most evident in his innovative low camera angles, deep focus techniques, and mise en scène compositions.

Ashes and Diamonds opens in the spring of 1945, somewhere in the Polish countryside, immediately after the end of the war in Europe. Two men lie in the grass outside a chapel, seemingly complacent. We only realize there’s trouble brewing when a small girl asks one of them to open the chapel door for her, and he tells her to beat it. At that moment a third man hollers that a jeep is approaching on the road, and the men leap up, grab a pair of machine guns and kill the driver and his passenger in a hail of bullets. Minutes later, after the assassins have fled, two more men arrive in another jeep and discover the brutal murders. One is a new communist commissar named Szczuka (Zastrzezynski), who realizes that the bullets were meant for him and his driver. The inept gunmen had murdered two innocent factory workers.

The assassins, Maciek (Cybulski) and Andrzej (Pawlikowki), are members of the Polish Nationalist Home Army who had fought the Nazis but now are determined to prevent the Soviet backed communists from gaining control. The Home Army was officially dissolved earlier in ‘45, before the end of the war, and now are active underground. Maciek and Andrzej take refuge in a hotel lobby. Andrzej closes himself in a phone booth to call their commander (the “Major”) to tell him the assassination is accomplished—but then Szczuka himself walks in with his driver and blithely asks a stunned Maciek to light his cigarette. Andrzej now is forced to tell the Major that it was all a terrible mistake. The furious Major insists that they find a way to carry out the assassination. Since Andrzej is his superior officer, it falls to Maciek to do the deed. He takes a room in the hotel next to Szczuka’s to await his chance.

Andrzej and Maciek (who is always in dark glasses) encounter Szczuka numerous times that evening. He no longer seems a faceless bureaucrat but a genial bear of a man. “Must we kill him?” Andrzej asks the Major. It appears there’s no way out of this assignment. Worse, when Maciek checks into his room next door to Szczuka, he sees a woman in a window across the courtyard wailing in grief for the two men he’s mistakenly murdered.

“Must I keep killing and hiding?” he asks Andrzej. Again, no answer. A merciless war is finished, but this new fight is just beginning. In a striking scene at the hotel bar, Maciek sets up a dozen glasses of vodka and sets them afire like votive candles for his honored dead comrades. He’s seen enough blood. Meanwhile, he’s begun dallying with an attractive blond barmaid, Krystyna (Krzyzewska), and lures her to his hotel room. Their sudden relationship is central to his efforts to deflect his agony over what he’s done and what he’s being forced to do.

Cybulski and Krzyzewska

With the war’s end, everyone seems to be trying—especially with booze—to get their spirits out of a ditch. A long table in the hotel dining room is set for a celebratory banquet; the town’s dignitaries are invited, including the mayor, as well as representatives of Soviet military. It turns into pandemonium when it is crashed by boorish locals half drowned in vodka. We see that it’s going to be a daunting task to bring order to Poland.

Wajda uses the relationship of Maciek and Krystyna to illustrate the depth of Poland’s tragedy, beyond all the death and destruction. She is a survivor, a breathing example of the fair and innocent who wonder how and why they survived the previous years-- her father died in Dachau, her mother in the Warsaw Uprising. Now, she says, she’s incapable of loving. Life is complicated enough. “Why complicate it further?”

“Any other family?” Marciek asks.

“Fortunately, no.”

He also has no surviving kin.

Why, she asks, does he always wear dark glasses?

“A souvenir of unrequited love for my homeland.”

Cybulski was often called the James Dean of Poland, and it’s obvious that he’d studied the American actor. You can see it in his posture and the cocking of his head when he leans against a wall with his cigarette, and in his death scene when he stoops, pulling his arms in under his ribs like Dean does in the police station in Rebel without a Cause. And then, of course, there’s his fatalistic volatility.

One curious thing that cannot be missed is the appearance late in the film of a white horse. What is it doing there? It seems to belong to no one and can’t have simply wandered arbitrarily into the film. Were it an ordinary brown or chestnut horse it might mean almost nothing. Does it have an apocalyptic meaning? Maybe. But unlike the white horse in the Book of Revelations, it is riderless— no god, hero or avatar of any kind is astride the handsome beast. Maybe Wajda is telling us that the white horse is there and riderless because, following all the terrible events of the war, Poland has found itself wandering with no clear surviving heroes.

And there is a famous scene where Marciek and Krystyna are out walking and find a figure of Christ dangling upside down from a bombed church. Of course, this can be interpreted in a hundred ways. Paul Coates argues that it displays a “Buñuelian blasphemousness,” and an “existentialist absurdity,” as opposed to a Marxist judgement of religion. However, I think it builds on the question posed in a poem by Cyprian Norwid that that Krystyna finds etched on a nearby wall, from which the title of the novel and film is drawn. The poem asks if ashes are all that is left, or will ashes hold the diamonds of eternal triumph?

Krystyna breaks a heel on the rubble. Marciek goes into a chapel to use a candlestick to hammer it back in place, but there he discovers under a sheet the bodies of the two men he’d murdered outside of town. Like the scene of the mourning woman in the window, this discovery torments him, and seems to push him to finish the job he was ordered to do so that he can get out of town forever.

But I think we have to wonder how our contemporary response to the film--and to Wajda’s earlier Kanal where resistance fighters crawl through the city’s labyrinth of sewers to escape German soldiers--must differ from his Polish audience of the 1950s, or other European audiences of the time still living in the rubble of the war. Although Wajda made this film thirteen years after the end of World War II and knew that stability of a kind followed, he was under no illusions. He became a leader in a later period of Polish filmmaking known as “The Cinema of Moral Anxiety” (1976-1981), a reaction to the communist crackdown on art and human rights. As for the Home Army, tens of thousands were arrested in the period following the war and sent to prisons in Russia.

Yet there is an optimism in Ashes and Diamonds, which some critics call the greatest Polish film of all time. I think it can be seen, paradoxically, in the implied failure of the counter-revolutionary Home Army—yes, the assassination is carried out, but it appears meaningless. As Szczuka lies dying on a muddy street, a display of fireworks erupts in the distance, reflected in the puddles. Does it represent the diamonds? It will end shortly, and the inebriated pyrotechnicians will stumble home. However, it is metaphorically important that the comically disrupted banquet goes on; and the rascals who threw the dinner into havoc end up banished to the latrine in the hotel’s cellar. Ignorant of the death of Szczuka, the hotel guests engage in a jovial polonaise, a celebratory folk dance. Where there’s a will to dance, there must be a future.

Sources and Paths to Further Exploration:

Coates, Paul. “Ashes and Diamonds: What Remains.” Criterion Collection essay, Aug. 24, 2021. https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/7506-ashes-and-diamonds-what-remains.

Coates, Paul. The Red and the White: The Cinemas of People’s Poland. Wallflower Press, 2005.

Insdorf, Annette. Ashes and Diamonds, commentary, Criterion Channell, 2004. https://www.criterionchannel.com/videos/ashes-and-diamonds-commentary

McDermott, J. J. “ The European Masterpieces Part 3: Ashes and Diamonds (1958 Andrzei Wajda)” Momentary Cinema, March 30, 2018. https://momentarycinema.com/2018/03/30/the-european-masterpieces-part-3-ashes-and-diamonds-1958-andrzei-wajda/

Nicholson, Ben. “Where to Begin with Andrzej Wajda: A beginner’s path through the Polish masterpieces of Andrzej Wajda.” BFI British Film Institute. 4 March, 2016. https://www.bfi.org.uk/features/where-begin-andrzej-wajda.

Thanks to Barry Voorhees for editing.

Thanks to Tim Madigan for suggestions.

Classic Film Capsules:

All the King’s Men (1949). Directed by Robert Rosen. With Broadrick Crawford, John Ireland, Joanne Dru. Black and White. 1 hr. 50 mins. Streaming on Prime and Tubi.

Adapted from Robert Penn Warren’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel of the same title, All the King’s Men is based on the political career of Huey Long, governor of, and later senator from, Louisiana. Willie Stark (Crawford) is a loveable—and barely literate— grassroots populist who wins election as governor by appealing to the sentiments of the state’s impoverished and disgruntled working people, promising to root out corruption. In office, he laudably expands government programs for the poor, and for public works projects. But he becomes corrupt himself. Blatantly ignoring legal processes, he becomes a law unto himself while never losing his ardent supporters. Everyone he touches, well-meaning or not, is corrupted, as he demands absolute loyalty and destroys everyone who gets in his way. Sound familiar? To paraphrase Bishop Butler, vice wears the cloak of virtue. He is impeached, but the state’s senate fails to convict him. Probably the best performance by Crawford, who became better known to the public as the star of TV’s Highway Patrol.

Taxi (1931). Directed by Roy Del Ruth. With James Cagney, Loretta Young, George E. Stone, David Landau, Berton Churchill. Black and White. 1 hr., 9 mins. Streaming on Prime and Max.

This is not one of James Cagney’s best films by a long shot. But it is entertaining, and has a great cast. Cagney plays Matt Nolan, an independent cab driver fighting off a gangster -led competing taxi company. But his worst enemy is his own temper. Loretta Young is his longsuffering wife. It is the one in which he growls the notorious lines: “Come out and take it, you dirty yellow-bellied rat, or I’ll give it to you through the door.” It’s also famous for Cagney speaking fluent Yiddish to a man on the street. George Raft has a bit part as a dancer whom Cagney punches in the kisser. David Landau, who usually plays a creep, is the murderous Buck Gerard. Judge West is played by Berton Churchill who was the embezzling banker in Stagecoach (1939).

Quotes:

“I got a part as a chorus girl in a show called Every Sailor and I had fun doing it. Mother didn't really approve of it, though.” —James Cagney

“My childhood was surrounded by trouble, illness, and my dad's alcoholism, but … we just didn't have the time to be impressed by all those misfortunes. I have an idea that the Irish possess a built-in don't-give-a-damn that helps them through all the stress.” —James Cagney

Text copyright 2025 by Steven Huff

All images are from public domain sources.