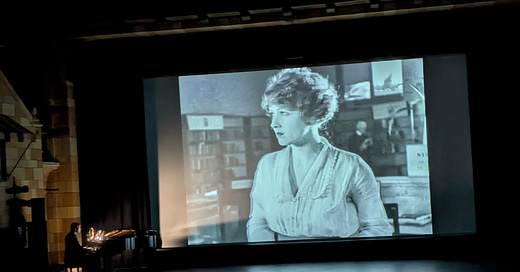

Last month I went to the Vintage Film Festival (Oct. 18-20) at the Capitol Theatre in Port Hope, Ontario, Canada. It’s a great fest that’s been run for thirty-one years by a remarkable and energetic group of people, and I urge any classic film lover to go when it happens again next October. Among the thirteen movies presented this year were West Side Story (Robert Wise, 1961), The 39 Steps (Alfred Hitchcock,1935), Sherlock Jr. (Buster Keaton,1924), Tokyo Story (Yasujiro Ozu,1953), Cleo from 5 to 7 (Agnes Varda,1962), The Blot (Lois Weber, 1921), and Key Largo (John Huston, 1948), a very eclectic mix. Most of them I’d seen before, but what a pleasure to see them on the big screen! The Capitol Theatre was built in 1930 to accommodate crowds for the new talkies, and has been restored to its original glory, actually one of the loveliest theaters I’ve ever walked into.

The picture above is from The Blot, with Jordan Klapman accompanying the silent film on piano. The film’s director, Lois Weber, was one of the first women directors, and one of the most successful of any directors during the 1920s.

But my immediate objective, in this issue, is to make you cry, with Make Way for Tomorrow.

Making a Stone Cry: Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow

By Steven Huff

Make Way for Tomorrow (1937). Directed and produced by Leo McCarey. With Beulah Bondi, Victor Moore, Thomas Mitchell, Fay Bainter, Maurice Moscovitch, Louise Beavers, Elisabeth Risdon. Screenplay by Vina Delmar, adapted from a play by Helen and Nolan Leary, which was adapted from a novel by Josephine Lawrence. Cinematography by William C. Mellor. Music by George Antheil and Victor Young.

Streaming on Criterion

For a long time, I have been wanting to write about Leo McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow because the movie affected me so deeply when I saw it the first time. It still throws me. But it’s been unavailable for streaming. Now, finally, it’s offered on the Criterion Channel— if you don’t have a subscription there, I highly recommend it. It’s inexpensive and wonderful for classic film lovers.

Make Way for Tomorrow begins somewhere in the Northeastern United States, during the Great Depression. An elderly couple, Lucy (Bondi) and Barkley Cooper (Moore), are losing their home for falling behind on their mortgage. Barkley has been out of work for several years. They call four of their five middle-age children together to tell them the sorry news (the fifth lives in California, and can’t attend); and that the bank has given them six months to get out. One asks, when is the six months up?

“Tuesday,” Barkley replies.

There are gasps all around. The siblings fall over each other trying to decide what to do. Mind you, none of them are out of work. But no one is able to take them both into their homes. They have, well, lives. Busy homes. The awful decision is made to split them up, at least “for now.” They’ll be in separate homes about three-hundred miles apart. The old couple is broken-hearted, and feel punished, but try to keep a bright mien. Barkley goes to their daughter Cora (Risdon), while Lucy goes to George (Mitchell) and his wife Anita (Bainter). Only George seems conscientious about it, which gives him a plague of anxiety when it becomes impossible to integrate his mother into his family in their New York City apartment. We get the sense that he was always the family’s good boy.

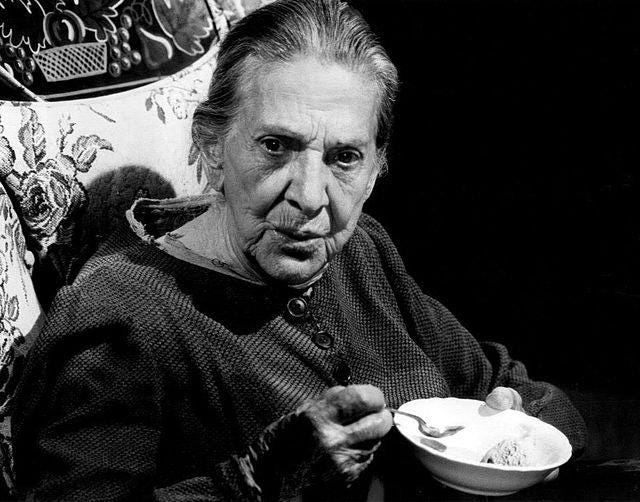

Beulah Bondi

Things go badly from the get-go. Lucy has a way of imposing herself and agitating. Anita teaches bridge in their home—her students are upper crust and come to class in tuxedos and gowns—and Lucy butts into the games. She takes a phone call from Barkley during the class, talks loudly, and has a heart-breaking conversation that puts a pall over the room. “I miss you, Bark, that’s the only trouble,” she tells her husband. “But we’ll soon be together….” She knows she’s being a bother, but she can’t seem to help it. As Roger Ebert points out, Bondi isn’t simply playing her role for our sympathy; “We catch ourselves thinking she really is a nuisance. She might get on our nerves, too.” Barkley, at Cora’s, is a bit of a nag and a manipulator, playing sick to get his daughter’s attention.

In an unforgettable scene, George must inform Lucy that she will go to a “rest home.” Lucy knows it’s coming, and interrupts him, asking to go. “I haven’t been happy here.” He knows that she is trying to make the inevitable easy on him. David Thomson calls it “one of the unkindest and most understandable scenes in American film,” because George has no other choice. Lucy has turned his wife into a nervous wreck. And one night their daughter Rhoda doesn’t come home. Who has she been running around with? They don’t know because she no longer brings boys home for her grandmother to give them a critical eye and embarrass her.

Meanwhile, Barkley plays sick one too many times and now he’s being sent to his daughter Addie in California for the climate. Lucy and Barkley will be a continent apart. Both sadly accept what they realize is the inevitable outcome.

In the last half hour of the film they get an afternoon alone together in New York before he has to get his train. The siblings are putting a dinner on for them, but they won’t show up. Instead, they go to the hotel where they went for their honeymoon fifty years before. They dance the time away. In Penn Station they say their goodbyes, with words like, “If…I never see you again….”

One of the great moments in film, I mean, anywhere or any time, is Beulah Bondi’s face as she watches his train roll away, then finally turns to go.

Orson Welles told Peter Bogdanovich that Make Way for Tomorrow was the saddest film ever made, and that it “would make a stone cry.” It reminds me of the final scene in The Trip to Bountiful (Peter Masterson, 1985) where Geraldine Page, in her role as an elderly runaway, is caught, and sitting in the backseat of her son’s car. The look on her face is saying, Oh, my God, this is the end. Watch that one if you want to cry some more.

Adolph Zukor, who in 1937 was chairman of the board at Paramount, came to the set of Make Way numerous times, pressing McCarey to give the story an uplifting finale. McCarey, however, was determined to end the film with what for its time was an uncharacteristically sad ending. As Zukor feared, the movie lost money. It might have been profitable if McCarey had allowed it to descend into sentimentality. Instead, he made a classic film—a timeless one, in fact, because what happens to Barkley, Lucy and their family is too familiar in American life.

Beulah Bondi, one of my favorite actors of that era, often played women older than herself. She was only five years older than Thomas Mitchell, who plays her son in Make Way. Most film lovers remember her as the mother of George Bailey (James Stewart) in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). She wanted the role of Mama Joad in The Grapes of Wrath, but it went to Jane Darwell. Mitchell, a great character actor and veteran of more than a hundred movies (he won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for John Ford’s Stagecoach), turns in one of his finest roles as George, the conflicted son—trying to be good to his mother, trying to keep peace in his family. Victor Moore gives one of his few dramatic performances as Barkley. Better known for comedy, he began his career in Vaudeville and finished with Billy Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955).

Louise Beavers and Fredi Washington in Imitation of Life (1934)

Louise Beavers, who plays George and Anita’s maid Mamie, has played a domestic many times. But Jazz and film critic Gary Giddens points out that McCarey gave Beavers a role she was not accustomed to playing. Her character in Make Way has more agency, as when she tells Anita that since she’s had to look after Lucy in addition to her other duties, she no longer has her nights free. After all, she has a life too. If this continues, she tells Anita, she’ll have to seek other employment.

Make Way for Tomorrow, as a serious drama, stands apart from much of McCarey’s work. He directed Laurel & Hardy, Charley Chase, Marx Brothers slapsticks, and romantic comedies of the thirties and forties. Even his dramas, such as Going My Way (1944) and The Bells of St Mary’s (1945) have threads of humor. Considered an actors’ director, he typically put them at ease, encouraged them to ad lib, and sometimes told them to play scenes their own way without a script.

To my mind, Going My Way, Bells of St Mary’s, and Make Way for Tomorrow demonstrate McCarey’s deep empathy for humanity. He made two films in 1937: Make Way, and the now-famous comedy The Awful Truth with Cary Grant and Irene Dunne. He received the Best Director Oscar for Awful Truth, which he richly deserved. In his acceptance speech however, he thanked the Academy but said that they had given it to him for the wrong film. Make Way was and remained his favorite, but he knew that, despite overwhelming critical praise, audiences stayed away because the subject was a little hard to bear.

Leo McCarey

Does a movie like Make Way teach us anything about ourselves? I think it must. It is said to have inspired Yasujiro Ozu’s masterpiece Tokyo Story (1953). But few movies make the attempt anymore. Twenty-some years ago, Phillip Lopate wrote, “The older direction, to plumb the lives of ordinary Americans for stories about their daily struggles, seems no longer an attractive alternative to filmmakers.” Yet not entirely so. Recently I saw Azazel Jacobs’s His Three Daughters, a story about spitefully estranged sisters who gather at their dying father’s apartment to sit out his last days. A powerful film, I have to say, without stars and with an obviously low budget. (It’s streaming now, on Netflix.)

Criterion offers Make Way for Tomorrow in a featured collection of films with women screenwriters. Although there were few women directors working in Hollywood in the ‘30s (really, only Ida Lupino and Dorthy Arzner), there were many women pounding out screenplays. Among these were Vina Delmar who wrote the screenplay for Make Way, from a play by Helen and Nolan Leary, adapted from a novel by Josephine Lawrence. Delmar also wrote the screenplay for The Awful Truth, and for twenty-five other films in addition to novels and short fiction. Her best-known novel was Bad Girl.

Other Notes:

Pianist and composer George Antheil, who scored Make Way for Tomorrow with Victor Young, worked with Hedy Lamarr on a cryptography system to protect allied communications in WWII. The system is still in use today for computer security.

Cinematographer William C. Mellor also shot The Great McGinty, Giant, Peyton Place, and won Oscars for A Place in the Sun and The Diary of Anne Frank. He died of a heart attack while filming The Greatest Story Ever Told, so he probably went to heaven.

Quote:

“I was a problem child, and problem children do the seemingly insane because they are trying to find out how to fit into the scheme of things.” --Leo McCarey

Sources and Paths to Further Exploration:

Bogdanovich, Peter. “Tomorrow, Yesterday, and Today.” Criterion Channel film commentary. www.criterionchannel.com/videos/tomorrow-yesterday-and-today

Ebert, Roger. “A Depression-era story of old age, tough and level in its gaze.” Roger Ebert.com. www.rogerebert.com/reviews/make-way-for-tomorrow-1937

Giddens, Gary. “On Make Way for Tomorrow. Criterion Channel film commentary. www.criterionchannel.com/videos/gary-giddins

Lopate, Phillip. Totally Tenderly Tragically: Essays and Criticism from a Lifelong Love Affair with the Movies. Anchor Books, 1998.

Thomson, David. Have You Seen…. A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films. Alfred A Knopf, 2008.

Uhlich, Keith, “Review: Make Way for Tomorrow. Slant magazine, July 8, 2004. www.slantmagazine.com/film/make-way-for-tomorrow/

“Vina Delmar; Adapted ‘The Awful Truth’ for the Screen.” Obituary, Los Angeles Times, Jan. 28, 1990.

All images are from public domain sources, except the first image: photo by Steven Huff.

Many thanks to Barry Voorhees for editing.

Text copyright 2024 by Steven Huff

Another wonderful entry. I love Thomas Mitchell Thank you for reminding me that there are wonderful films out there I have yet to see. Antheil composed the music for Ballet Mecanique.