My apologies! I’m a day late this time with The Moveable Marquee. But I’m late on purpose. I’ve decided not to post on holidays, as I don’t think many people read their email on those days. I’m talking about big federal holidays, of course, not Halloween or Groundhog Day. Henceforth, if one of my usual publication dates—the first and the fifteenth of the month—lands on a holiday, I’ll post the following day.

And Happy New Year to all! The Moveable Marquee enters its third year.

In this issue, I’m focusing on a great silent film that I’ve seen numerous times: The Docks of New York. It always seems fresh.

CONTENTS OF THIS ISSUE:

1 Grace in Mayhem: Commentary on The Docks of New York.

2 Book Review: A Complicated Passion: The Life and Work of Agnès Varda, by Carrie Rickey.

Grace in Mayhem, Josef von Stroheim’s The Docks of New York

By Steven Huff

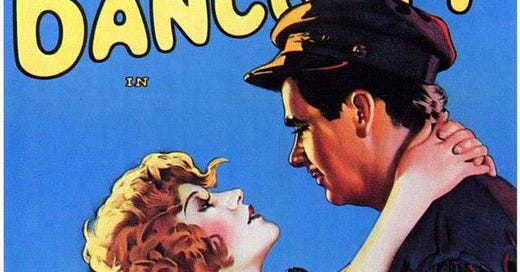

The Docks of New York (1928). Directed by Josef von Sternberg. With George Bancroft, Betty Compson, Olga Baclanova, Clyde Cook, Mitchell Lewis, Gustav von Seyffertitz. Written by Jules Furthman. 2010 Score by Robert Israel. Black and White. Silent. 1 hour, 16 minutes.

Streaming on Criterion, Prime and YouTube

Jonas Stern (1894-1969) was a child of an Orthodox Jewish laborer who dragged his family from Vienna to New York and back, unable to make a decent living in either place. Perhaps early poverty fostered insecurity that provoked Jonas’s storied arrogance and malignant temper in his professional life as a filmmaker. Suffice it to say, for actors and crew, he wasn’t easy to work with. Along the way he became Josef Sternberg and added the von for its baronial cache—another marker of insecurity. After various humbler jobs, the young man found work in the US and England as an assistant director, scenarist and cameraman. In World War I he made training films in the US Army Signal Corps. He made his own first feature film, The Salvation Hunters, in 1925, an independently produced film with a poverty budget.

It was his good fortune that the film impressed Charles Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks, who advocated for him to the big studio moguls.

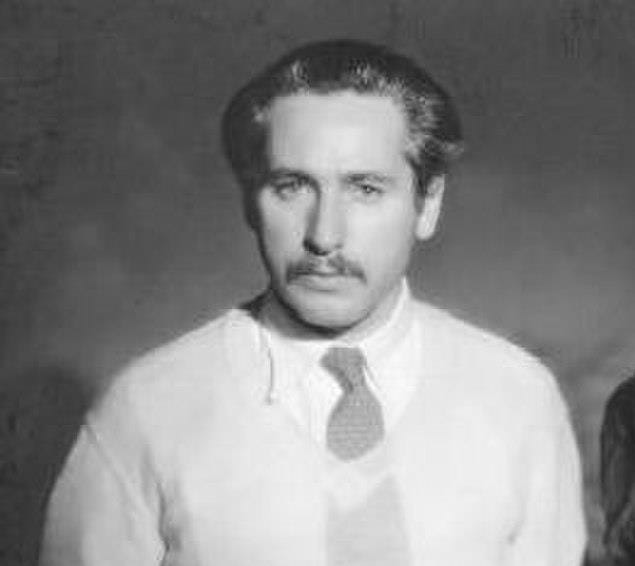

Josef von Sterberg

Von Sternberg (I’ll call him that for the rest of this piece) made a number of fine films in the silent era, including some that are classics. Underworld, often called the first feature-length gangster film, was hugely successful and influential and made von Sternberg famous. Its shootout scene near the end clearly influenced the one in Howard Hawks’s Scarface (1932). The Last Command (1928) is a heartbreaking story of a Russian general (Emil Jannings) in the Czar’s army who, after the Revolution, finds himself in Hollywood in demeaning bit roles. Both are good stories, wonderfully well-shot and directed. Von Sternberg didn’t go in for color tinting, which was popular in the silent era—they’re straight forward black and white.

His first sound film, Thunderbolt (1929), was a stumbler. Similar to Underworld, it’s about a bullying gangster (George Bancroft) who loses his girlfriend to a decent man who offers her a better life, but gets arrested and sent to the gallows before he can kill the other guy. But it was the early days of sound, the voices are a little hollow, and as with many films at that time, there seems to be a three-second lag between speakers.

Von Sternberg went to Germany for his next film, The Blue Angel (1930), probably his most famous, which was also the beginning of his association with Marlene Dietrich. According to Budd Schulberg, he became her Svengali. Anyway, she followed him back to Hollywood for a string of films, Morocco (1930), Dishonored (1931), The Shanghai Express (1932), and Blonde Venus (1932). They’re all classics, and any film lover should see them, although I find Morocco disappointing for its absurd ending in which Dietrich, playing a classy cabaret singer, is outfoxed in love by French legionnaire Gary Cooper and ends up a camp follower when his brigade marches off. She has to take off her spike heels so she can trek barefooted over the North African sand. She couldn’t have liked that ending either. Blue Angel was also the first talkie for Emil Jannings, who had fled back home to Germany when sound came in, thinking that his thick German accent would prevent him from getting good roles in the US.

Shanghai Express (1932), one of the best of the genre of train capers (such as Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes and Walter Forde’s Rome Express), was probably von Sternberg’s most visually exotic film and includes the iconic frame of Dietrich’s alluring face in a train window.

But now I’m coming around to my focus: The Docks of New York (1928). I think it’s the best of von Sternberg’s silents. Superb storytelling, sensuous realism, visual richness, together with its themes of love, humanity and unexpected grace in the very dregs of society, make it a solid classic.

The opening shots on a gray day in New York Harbor set an appropriately bleak mood. We see the coal stokers feeding the flames in the ship’s fire room, a hellish operation. After the ship docks the men are told they have a single night ashore; the ship will sail again in the morning. It’s dark by the time the sailors step off the boat in a dense fog. As Bill (Bancroft) is sauntering along the dock heading for the Sandbar saloon, we see a woman on a high walkway-- and we see her jump. When Bill notices her floundering in the frigid water, he casually takes off his jacket and hat—what’s the hurry?—then jumps in after her and pulls her to shore. While women from the bar work to revive her, he is sent to get her a hot toddy. He cares more than he lets on, and he breaks into a closed pawnshop to bring her some dry clothes.

Mae (Betty Compson) and Bill (George Bancroft). He’s just dumped dry clothes on her bed

When you first encounter George Bancroft on screen, he might appear cut from the same rough mold as Victor McLaughlin or Wallace Beery. But he is far more subtle and nuanced, and therefore more sympathetic than either of them. Von Sternberg had already made him a star in Underworld, and casting him in this role almost guaranteed Docks of New York would be successful. Betty Compson, as the suicidal Mae, projects the cynicism of a Marlene Dietrich. After the women have thawed her out and put her to bed in her room, she smokes and snarls her invective: why didn’t they just let her drown?

Yet Bill wants to show her a good time. “I’ve had too many good times,” she growls.

He convinces her to meet him in the Sandbar, a rough place where hookers abound, and fights break out about every six minutes. When Mae shows up, Bill has to deck a couple of guys, including the engineer from the ship, to keep their drunken hands off of her. After a ten-minute courtship, Bill has a sudden moment of grace and chivalry: he decides to marry Mae— immediately, right then and there. Mae, for all her incertitude, agrees. They send for a waterfront preacher named Hymn Book Harry (von Seyffertitz).

A bawdier, more chaotic wedding with shrieks of hilarity has probably never been filmed. You realize that the film is in the hands of a master, that such an event could be made believable: A woman who tried to drown herself only a couple hours earlier is now getting married in a bar to a man she had just met, who in fact had pulled her out of the water. It seems not only possible but true. Tag Gallagher in Senses of Cinema, speaking of von Sternberg’s oeuvre in general, wrote, “In no other cinema, except perhaps Murnau at times, do people seem more present on the screen [Italics Gallagher’s]. Curiously they all wear masks, which reveal their nakedness.”

But Bill has only known one life—at sea. His vow sounds a little shaky (instead of “I do,” he says, “Sure, I will”), but Mae is holding onto it for dear life. She says, “You don’t know what this means to me, Bill.” Will he honor his vow? Will he stay ashore with Mae, or will he sneak aboard ship the next morning? How much can such a man change? Or can he change at all? It’s not your usual love story; in fact, it is an extraordinary affair of the heart. And it will not come to the ending that you might expect. The Docks of New York, for all the bawdy goings-on, goes into the soul of Bill and Mae, exposing not only their pasts of lust, cynicism and deceit, but their deeper hunger.

The sets for Docks of New York are aesthetically lush and wonderfully textured: the moody fog, the fiery pit where the stokers work, the carnival chaos in the Sandbar, the cracked plaster walls of the prostitutes’ rooms. I’ve seen this movie several times and I could happily watch it again, anytime. It’s not a film you can watch only once.

SOURCES AND PATHS TO FURTHER EXPLORATION

Card, James. Seductive Cinema: The Art of Silent Film. Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

Clark, David. A History of Narrative Film. 4/e. W. W. Norton and Co., 2004.

Gallagher, Tag. “Josef von Sterberg.” Senses of Cinema, Issue 19, March 2002.

Schulberg, Budd. Moving Pictures: Memories of a Hollywood Prince. Ivaan R Dee, 1981.

Silver, Charles. “Josef von Sternberg’s The Docks of New York. INSIDE/OUT: A MOMA/MOMA Ps 1 Blog May 11, 2010.

Thomas, David, The New Biographical Encyclopedia of Film. Alfred A. Knopf.

Book Review

A Complicated Passion: The Life and Work of Agnès Varda, by Carrie Rickey. W. W. Norton and Co. 288 pp. ISBN-13 : 978-0393866766. Cloth, $29.99. Also available in Kindle and Audible. Paperback not yet published.

Anyone who pays attention to the careers of motion picture directors has a fairly clear idea of the usual paths to those lofty positions. Nowadays, most aspiring directors go to film school. Some in the past started as screenwriters, or camera assistants who worked their way up to assistant director. Rarely does anyone simply borrow a camera and start a career as a director. At the very least, a director is the product of a long love affair with film. Carrie Rickey’s excellent biography, A Complicated Passion: The Life and Work of Agnès Varda, describes the very unusual path of a woman who, at age twenty-five, simply decided to make a film.

No cinephile in her youth, Varda (1928-2019) was 25-years old and had seen no more than twenty-five movies when she made her first film, which might point to a level of natural genius. Anyone can learn how to use a camera on the job (Gregg Toland taught Orson Welles in an afternoon). But setting up shots, composition, and effectively telling stories in frames, as she seems to have done almost naturally, certainly drew from her previous work as a still photographer, her studies at the Louvre—and an innate brilliance.

Rickey tracks Varda’s long and determined life and career, her passions and setbacks, from a war-displaced childhood through the making of sixty-three films. When the Nazi’s invaded Belgium, Varda’s family fled south by car, living in various places including the seacoast town of Sète, where Agnès would later make her first movie, La Pointe Courte. It was filmed on the backdrop of a fishing village, among fishermen and their families that she had befriended when she was a teenager. In her early twenties in Paris she studied painting and sculpting, finally picking up a camera. Like most photography students, she worked at shooting weddings, Bar Mitzvahs and making baby portraits. And like most who studied photography before the digital age, the bathroom in her apartment doubled as a darkroom.

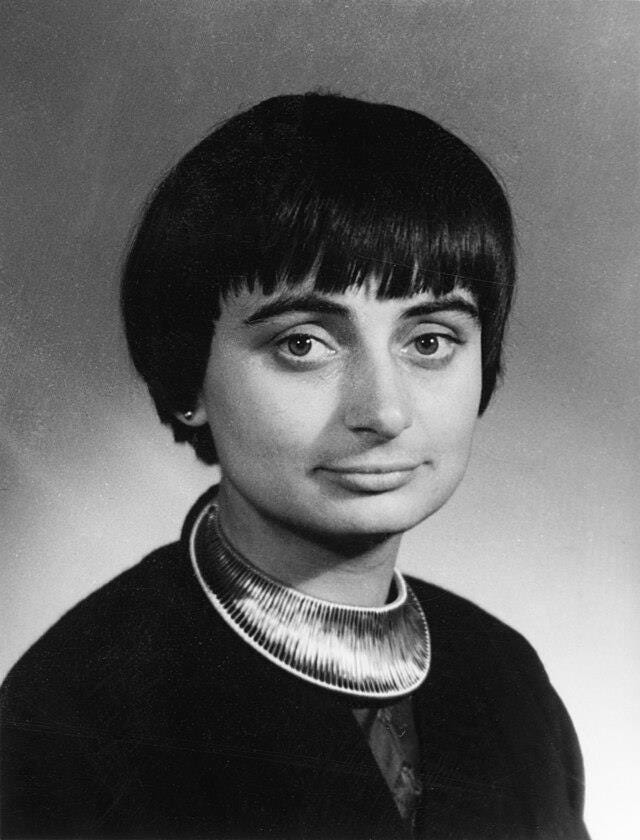

Agnès Varda

Poorly distributed upon its release, La Pointe Courte (1955) is now regarded not only as a classic of French cinema, but a forerunner of the French New Wave—coming years before the initial films by Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and other young filmmakers associated with the movement and with the famous film journal Cahiers du Cinéma. She had to use creative funding. She had a small inheritance of around $30,000, and she convinced actors (which included Silvia Montfort and Phillip Noiret) and crew to work for a share of the eventual ticket income—which meant that they received almost nothing. Conning Alain Resnais (before his Hiroshima Mon Amour) into helping her edit the film took a bit more finesse.

The later films that made her a legend of French cinema were Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962), Le Bonheur (1965), and Vagabond (1985), all stories well told. Among her features and documentaries were numerous personal films, which, taken together, give one a sense of knowing her quite well: her late film memoir, The Beaches of Agnes (2008); Ulysse (1983), a meditation on a photograph she made in the early 1950s of a naked man and boy on the ocean, sharing the frame with a dead goat; The World of Jacques Demy (1995), a tribute to her deceased husband, director Jacques Demy (who did go to film school, by the way); and Uncle Yanco (1967), in which she finds a long-lost relative living on a houseboat in California.

Yet, Rickey gives us a great deal more, filling in an abundance of details. There were Varda’s early struggles to be accepted as a lone woman in a profession that was almost entirely male-dominated; her struggle to find funding; the dozens of scripts she wrote that went unproduced; managing single-motherhood while utterly engrossed in her work; her marriage to Demy, who left her for a man he’d had a long-term affair with, eventually returning home with HIV, not long before his death in 1990 at age 59.

In her fictional films, we can see Varda in Cleo Victoir, the pop music artist in Cleo from 5 to 7 (possibly her greatest film), who struggles wth her own insecurities, worrying over the results of her cancer biopsy that she expects by the end of the day, and finding a level of inner security. In Vagabond, however, we see a younger homeless woman whose independence becomes a mental pathology that leads to tragedy. Varda got the idea for the story when she picked up a young woman hitchhiker who shared stories of her itinerant life, and from a news story about the rise in youth homelessness in France. The film, as Rickey notes, is structured a bit like Citizen Kane—first a dead body, then interviews with a series of people who the woman had met in her travels, exposing society’s attitudes, and sometimes outright disgust, toward the homeless. It is one of Varda’s most powerful films.

Initially, she and Demy were regarded as a rare power couple—two directors living together, which, Rickey points out, may have been the first such couple since the early days of film when French director Alice Guy was married to Herbert Blache, and American director Lois Webster was wed to Phillips Smalley. Although it should be said that those couples worked together on their films, while Varda and Demy were primarily involved in separate projects.

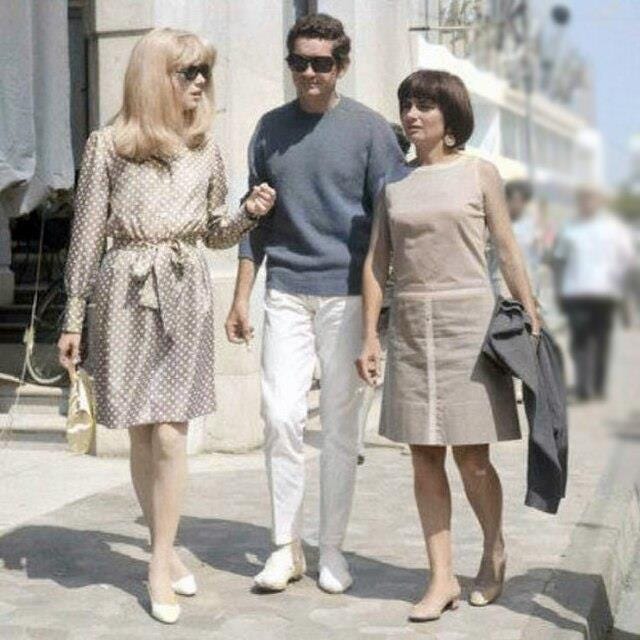

Demy unquestionably had more commercial success than Varda, with films such as Lola (1961), Bay of Angels (1963), and the musicals, The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) which some consider the best musical of all time. It was his trip to Los Angeles for the Oscars—Umbrellas of Cherbourg was nominated for five Oscars, including best foreign language film, but did not win in any category—that began their brief romance with Hollywood. While in the US, Varda made Black Panthers (1968), a documentary of interviews with Huey P. Newton, Stokely Carmichael, Bobby Seale and others. In LA, Varda formed a friendship with Jim Morrison of The Doors, which continued after he moved to Paris. She was among a cluster of his friends who kept his death from the press until there was time for a quiet funeral.

Catherine Deneuve, Demy and Varda on the set of The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

The overall picture of Agnès Varda that we get from Rickey is one of a determined woman artist, often going it alone when she couldn’t get support, who always bounced back from personal grief and from professional setbacks, to finally becoming a French national treasure, revered master, the guest at film festivals, a trailblazer who opened doors for and influenced women directors such as Jane Campion, Sofia Coppola, Kathryn Bigelow and others.

But I strongly recommend that, upon finishing Rickey’s book, one should cap it off by watching Varda’s afore-mentioned film-memoir, The Beaches of Agnès . It not only covers her life but is one of the most visually exciting film essays of its decade. Not quite her last film, but still a fascinating swan song.

--Steven Huff

All images are from public domain sources

Text Copyright 2025 by Steven Huff

Thanks to Barry Voohees for editing.