Issue # 50, July 15, 2025

Cineac Cinema and Heck Lunchroom at night, Rotterdam. (Ca: 1936-1940).

Contents of this issue:

Entrée: The Last Wave By

Film Commentary: “You Can Never Escape the Casbah”: Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le Moko.

Classic Film Capsules: A Monkey in Winter, The Parallax View, Five Star Final

Quote

Entrée: The Last Wave By

People who grew up in the fifties and sixties as I did are among the last wave of movie goers who went to single screen theaters. I mean, when single screens were the whole biz. It was the last hurrah before the arrival of plaza multi-screens and all that came after: dvds, streaming, etc. The doting adults who dug in their pockets for the small change to send us to the pictures are gone, most of them. We saw the tail end of the B movies that ran on double bills with A pictures, plus, sometimes, a cartoon. It was the beginning of the end of the triple-feature drive-in theaters. Nothing in the world looks lonelier now than a closed-down drive-in: a field of disarmed speaker posts and a blank screen falling apart panel by panel. (Imagine how many children were conceived in those desolate lots.) We saw the finale of 3D. It was also the end of Cinerama, although few of us actually experienced that bloated extravaganza. It was a good thing that we didn’t know it was all about to change.

The old theaters had a mystique that cannot be recaptured any more than you can repeat last night’s dream. There were intriguing doors in our neighborhood movie house. One was probably just a janitor’s closet, but another opened to a stairway up to the resident magician in the projection booth. I never ventured up those stairs, nor did anyone else I knew. After seeing Cinema Paradiso, I wished that I had.

But the films that played in the old houses are not orphans now. Thank god for the preservationists. And I meet many young people who seem to love those movies as much as I do. There are opportunities to see old films projected on screens—in repertory theaters, mostly, and classic film fests. If you love old movies, you shouldn’t pass up an opportunity to watch a film projected as it was meant to be seen. I’ve been known to sneak into college classrooms where I’d heard they were going to screen a movie I wanted to see.

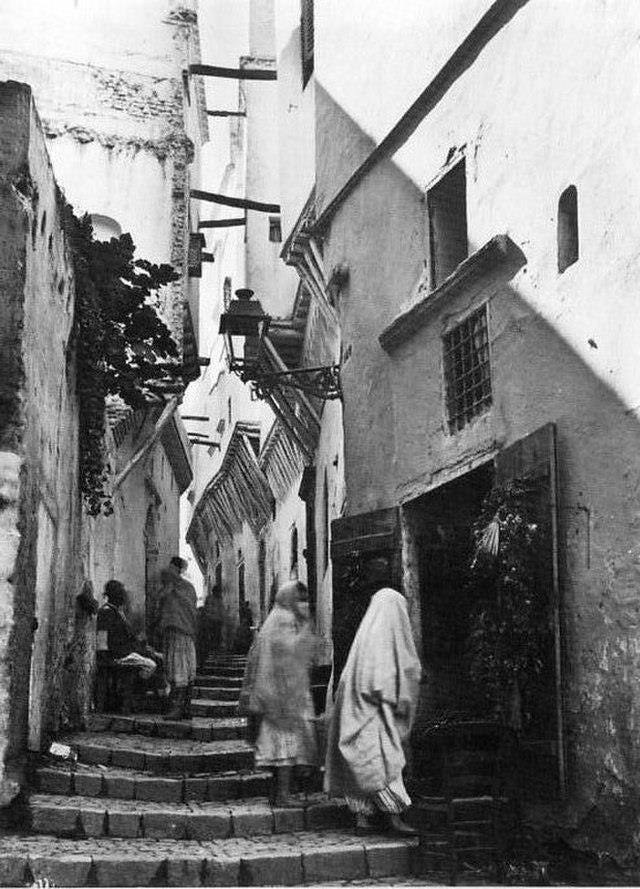

The Casbah, 1900

Film Commentary:

“You Can Never Escape the Casbah:” Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le Moko

By Steven Huff

Pépé le Moko (1937) Directed by Julien Duvivier. With Jean Gabin, Mireille Balin, Charles Granval, Fernand Charpin, Line Noro, Lucas Gridoux. Screenplay by Henri La Barthe, Julien Duvivier, Jacques Constant and Henri Jeanson, from the novel by La Barthe. Cinematography by Marc Fossard, Robert Hakim. Music composed by Mohamed Iguerbouchène and Vincent Scotto. Black and white. In French with English subtitles. 1 hr., 37 mins.

Streaming on Criterion

Every time I see Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le Moko, I’m struck by the “realism” of the Casbah, the principal location of the film, even though I understand that the scenes of that cramped quarter of Algiers, with its exotic, nefariously twisting alleys and passageways, were primarily shot in a Paris studio. Exterior scenes outside the Casbah were shot on the French seacoast of of Sète and Marseille rather than Algeria.

Duvivier (1996 – 1967) was one of the principal directors of French cinema’s Golden Age, the period from the beginning of sound films (1929 in France) until 1939 when the French dominated Europe’s film industry. He is also associated with the Poetic Realism style of that time. Directors of that era also included Jean Vigo, Pierre Chenal, Marcel Carné, and Jean Renoir (whose work really transcends categories). The above parameters are somewhat artificial, since some films of that movement were made later, during the Nazi occupation of France.

Poetic Realism refers to the way many films in that era created “realism” in the studio. Sometimes the sets were quite elaborate, such as the early nineteenth-century streets of Carné’s Children of Paradise, and the Casbah of Duvivier’s Pépé le Moko. The filmmakers of the later French Nouvelle Vague (New Wave) would, in contrast, insist on location shooting.

Julien Duvivier

Although his seventy films span almost fifty years, from 1919 to 1967, Duvivier’s best-known pictures are from this so-called Golden Age. They include Un carnet de bal (Dance Card, 1937), La bandera (Escape from Yesterday, 1935), and La belle equipe (They Were Five, 1936).

Pépé le Moko opens in the police office in Algiers where a group of French detectives are arguing with a police official from Paris who accuses them of inaction in rounding up one Pépé le Moko (Gabin), a notorious Paris thief and bank robber. He has taken refuge for the past two years in the Casbah, where it is almost impossible to find anyone who does not want to be found. “It is not child’s play,” a detective tells the churlish official.

The film then switches to the Casbah where Pépé, handsome and domineering, has become the local underworld chief with his own criminal gang. He supports himself by preying on wealthy women with dangling gems. Others vie for his favors, and warn him of sudden police incursions, which are usually a waste of time and bullets anyway. Pépé has a long string of women friends, jealous of one another. One woman remarks, “When he dies, there will be three thousand widows at his funeral.” So, it would seem, he has a capacity for intimacy, but not of a deeper kind. Or does he?

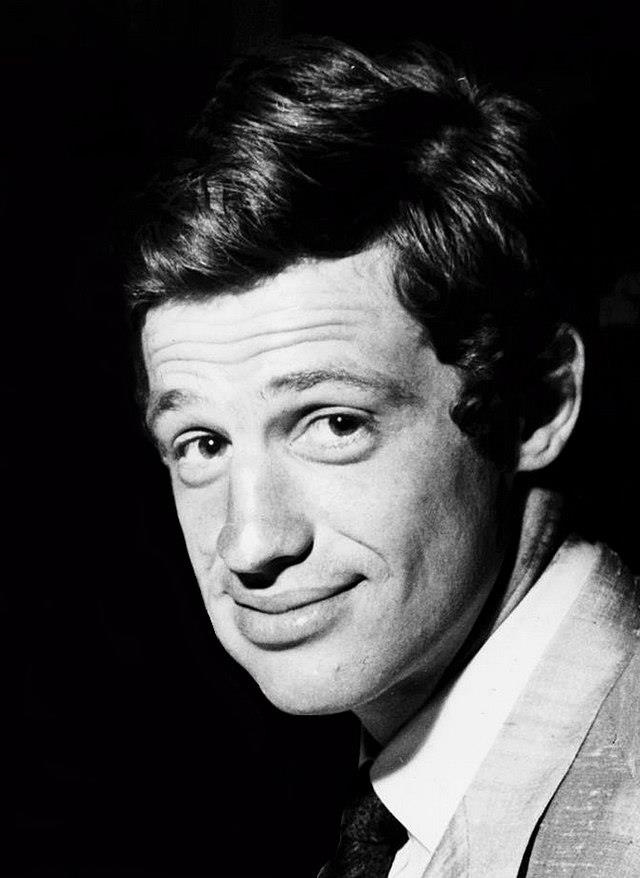

Jean Gabin

The steamily atmospheric Casbah is populated by Arab North Africans as well as ne’er-do-well fugitives and has-beens from around the world. It is also a destination for rich people on slumming expeditions: a gold mine for thieves and pickpockets. All of which raises the question of whether the film makes any comment on French colonialism. Perhaps nothing overtly stated. However, this quarter of Algiers is presented as an entirely amoral place where crookedness can operate unabated. Moreover, the principal players are European, and they’re dominant over Arab characters (or Europeans playing Arabs) who appear servile, save for Slimane (Gridoux), the sole Arab police inspector in the Casbah, an underhanded antagonist who feigns friendship with Pépé while waiting his chance to snare him, possibly symbolizing the Arab world coiling to strike.

But the Casbah has become a prison to Pépé. He’s homesick for Paris, for familiar civilization, but knows that if he sets foot outside the quarter, his next stop might be Devils’ Island, if he is not shot dead. His lover Inés (Noro), who is trying desperately to hold onto him, says, “You can never escape the Casbah. They want to arrest you. But you're already under arrest….One step out and it's ‘Good-bye, Pépé!’”

Mireille Balin

One day a stunning woman from Paris named Gaby (Balin) arrives with her much older lover, Maxime (Granval). Pépé zeroes in on her pearl necklace and diamond bling-bling. But then…he falls in love with her, hook, line and sinker. She embodies everything he loves about Paris, and he sees in high contrast what he has been missing these past two years. Although he lives with Inés, he begins an affair with Gaby, a misstep that will lure him out of his safe zone to the film’s perilous denouement.

John W. Martin comments that much of the film’s effect is due to Duvivier’s ability to evoke the atmosphere and intrigue of the Casbah. David Thomson said it was “shot and created with skills worthy of Michael Curtiz.” I’m guessing that he meant that Duvivier’s sets, and his seductive use of shadow and light, capture the intriguing exoticism that Curtiz accomplished in Casablanca. In fact, Pépé le Moko is said to have influenced Casablanca, although it is more of a fatalistic film noir than a romantic drama such as Curtiz’s film. Yet there are other similarities. Both were made on studio lots rather than in North Africa. Both became launch vehicles for their male leads, Gabin and Bogart, who, because of the success of those films, began landing leading roles with more regularity. Gabin became one of the greatest French film actors of his era.

Mireille Balin, a former fashion model in her first major film role, lacked the wholesome looks of Ingrid Bergman, but had the erotically angular features of Marlene Dietrich. She worked her way up to the A list of French women actors. But like Bergman she got in trouble over whom she slept with; in Balin’s case it was a Wehrmacht officer which put her career on a slippery slope after the war ended. She even served a short prison term for collusion.

Fernand Charpin

Another notable in the cast is Fernand Charpin, as Regis, a Casbah hang-about who is killed after he collaborates with police in a plot to nab Pépé, which instead causes the death of Pépé’s friend Pierrot. Charpin was an accomplished character actor in more than seventy films, including the role of the Marquis in Marcel Pagnol’s classic The Baker’s Wife with the great Raimu.

Other Notes:

In World War II, when he was with the US army in North Africa, future film director Samuel Fuller visited the Casbah. He wrote that it was “nothing like the one in Julien Duvivier’s Pépé le Moko….The place was nothing more than a squalid quarter in a big, bustling city.” Fair enough. But then, Duvivier’s Casbah is only poetic realism.

Pépé le Moko inspired the creation of the cartoon skunk Pépé le Pew.

Sources and Paths to Further Exploration:

Cook, David A. A History of Narrative Film, 4th ed. W. W. Norton, 2004.

Fuller, Samuel. A Third Face: My Tale of Writing, Fighting, and Filmmaking. Applause Theater & Cinema Books, 2002.

Martin, John W. The Golden Age of French Cinema 1929-1939. Columbus Books, 1983.

Morgan, Janice. “In the Labyrinth: Masculine Subjectivity, Expatriation, and Colonialism in Pépé Le Moko.” The French Review 67, no. 4 (1994): 637–47. http://www.jstor.org/stable/396926.

Thomson, David. Have You Seen…? A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films. Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

Travers, James. “Pépé le Moko (1937), Directed by Julien Duvivier.” Best French Films of the 1930s. www.frenchfilms.org/review/pepe-le-moko-1930s

Thanks to Barry Voorhees for editing.

Thanks to Tim Madigan for suggestions.

Classic Film Capsules:

Jean-Paul Belmondo

A Monkey in Winter (1962) Directed by Henri Verneuil. With Jean Gabin, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Suzanne Flon, Paul Frankeur. In French with English subtitles. Black and White. 1 hr., 45 mins.

I thought it appropriate to include another film with Jean Gabin, this one from late in his career. He had long since developed that rare screen presence of an actor who has merely to walk in front of the camera to grab the audience. The scene is a bucolic town on the northern coast of Occupied France where Nazis seem comfortably settled in. Albert (Gabin) and Suzanne (Flon) are innkeepers. One day while Albert and a pal (Frankeur) are getting gloriously drunk in a brothel, Allied bombers begin pounding the town so violently that Albert is certain that he—and everyone else--will die. He makes an oath that if he survives, he’ll never drink again. Then the story jumps ahead twenty years. Albert and Suzanne have survived, and he’s been as good as his word, staying dry. The inn does a quiet but substantial business and all seems well. Then young Gabriel Fouquet (Belmondo, two years after Breathless) checks in. He quickly proves himself a ribald instigator, and he slowly entices Albert and all his long-withheld deviltry into the street, culminating in a drunken fireworks display, the most excitement the town has seen since the bombing. A lyrically beautiful, hilarious film, with a poignant ending. Streaming on Criterion.

The Parallax View (1974) Directed by Alan J. Pakula. With Warren Beatty, Paula Prentiss, William Daniels. Color. 1 hr., 42 mins.

To fully appreciate the intrigue and fatalism of The Parallax View it is necessary to understand a bit about the era in which it was made. In 1974 the US had been through a decade of assassinations, Watergate and other political scandals and conspiracies. Public trust of government, and for that matter, corporations, was at an all-time low. This and other films such as Rage (1972) Three Days of the Condor (1974) and All the President’s Men (1976, also by Pakula), found ready and receptive audiences. Parallax is a faux security company that specializes in sabotage and assassinations, although we do not come to understand the full extent of their clientele. After the assassination of a popular US Senator, people who were present at the event begin dying mysteriously. Joe Frady (Beatty), a reporter with more than his share of personal problems, decides to investigate. Streaming on Prime and MGM+.

Edward G. Robinson

Five Star Final (1931) Directed by Mervyn LeRoy. With Edward G. Robinson, Marian Marsh, H. B. Warner, Frances Starr, Boris Karloff. Black and white. 1 hr., 29 mins.

A film with real teeth. Maybe the sharpest takedown of yellow journalism I’ve seen in a movie. In the old days of New York’s Park Row, The Gazette, a tabloid specializing in dirt, is engaged in a circulation war. City editor Joseph W. Randall (Robinson in one of his better early roles), learns that a woman named Nancy Voorhees (Starr), who was acquitted in a sensational murder trial twenty years before, is now married to a respectable man named Michael Townsend (Warner), and that her daughter (Marsh) is about to be married into a wealthy banking family. Starved for dirty news, he decides to run an exposé of her, turning her and her family’s lives tragically upside down. Boris Karloff is fine as an unscrupulous reporter who poses as a clergyman to get close to the family. It’s a visually interesting film with unusual framing for its time. Tension is ratcheted up in a short triple-split-screen part. Streaming on Prime.

Quotes:

“The sitting around on the set is awful. But I always figure that’s what they pay me for. The acting I do for free.” —Edward G. Robinson.

Text copyright 2025 by Steven Huff

All images are from public domain sources.